Train station platforms are a mounded blanket pile obstacle course; Little children wriggle out like Roos emerging from their mum's pouches, leaving a gap into a warm blanket pile of humans sleeping on humans.

We were 3 hours into a 5 hour wait at Moradabar for our train to Rishikesh. I still had the shits after 10 days and couldn't stop my nose from streaming. We were rapidly running out of any sort of tissue and a 'female' toilet was apparently nowhere to be found. An old man dressed smartly all in white with a black waistcoat and sharp eyes walked over and greeted us with quiet 'namaste' smiles. Ram Babu Kumar was his name. He said, 'I could sense that you were feeling unwell and became anxious to talk to you…' He checked that we had medicines and gave us a long, kind, look in the eyes. With more 'namaste' smiles he disappeared down the platform. Later that evening whatever illness it was that had been stewing around in my body evolved into a week long monster.

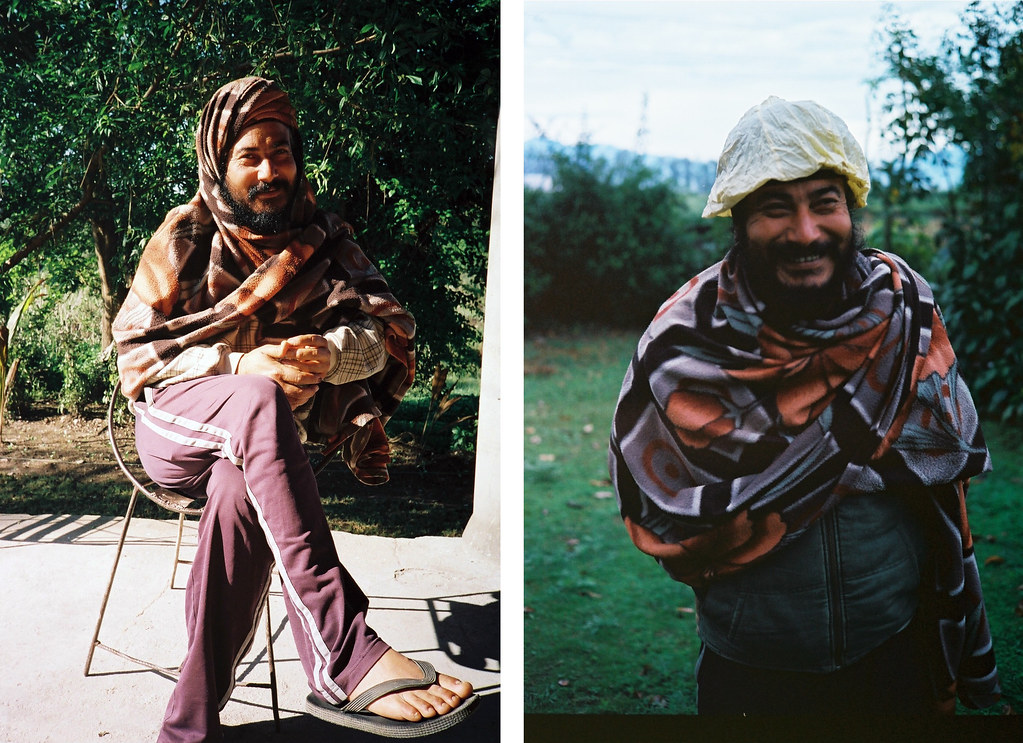

We met Mr Raju, a tall man in a tracksuit and a turban with a thick, combed, black beard, at the junction somewhere roughly 25km outside Rishikesh. He gestured with one slow, sweeping arm movement that our rickshaw driver should continue down a bumpy track, following him on his moped. Mr Driver was not pleased about this long, pot-holed addition to the journey that threw around his rickshaw and seemed with each corner to have no approaching ending. Constant head-roof / arse-bench crashing. I didn't know whether to laugh or cry, and by the sound of it neither did Mr Driver. Angus laughing (obviously). I might shit myself or vomit… Mr Raju miles ahead on his moped… We expected Mr Driver to ask for the extra that we'd haggled down on the price. Eventually Mr Raju stopped and so did we, preparing for disgruntled Mr Driver. We pulled up next to Mr Raju and the other tall man (his brother we later found out), with eyes that lit up when they smiled, deep laughter wrinkles and wide grins from behind their thick beards. They spoke just a few words and any bad feeling diffused into laughter, pointing him in the direction of a smoother way back to the main road.

A small village of pastel-coloured homes in fields of vibrant green, organic herbs and sugar cane, accessible only on foot, balancing along irrigation channels that edge the fields. Mountains to one side and a river that marked the beginning of the jungle where elephants and 'a leopard' live, to the other. Mr Raju has lived on the farm for all of his life, now with his wife and children, along with his parents and brothers and their families. A Sikh family. We slept in and worked around the newly-ish built, small block of rooms, painted earthy red with woven grass roofs - what would soon open as Nature Care Village, a retreat centre for natural healing and yoga. A young Nepalese couple, Khayam and Kalphuna lived there and were the cooks.

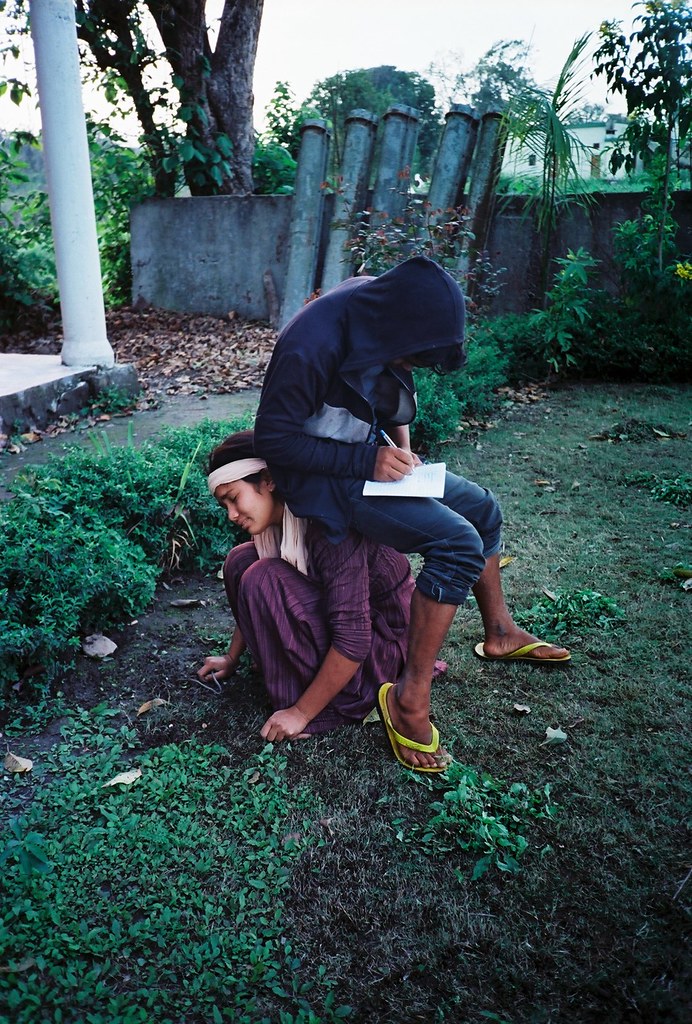

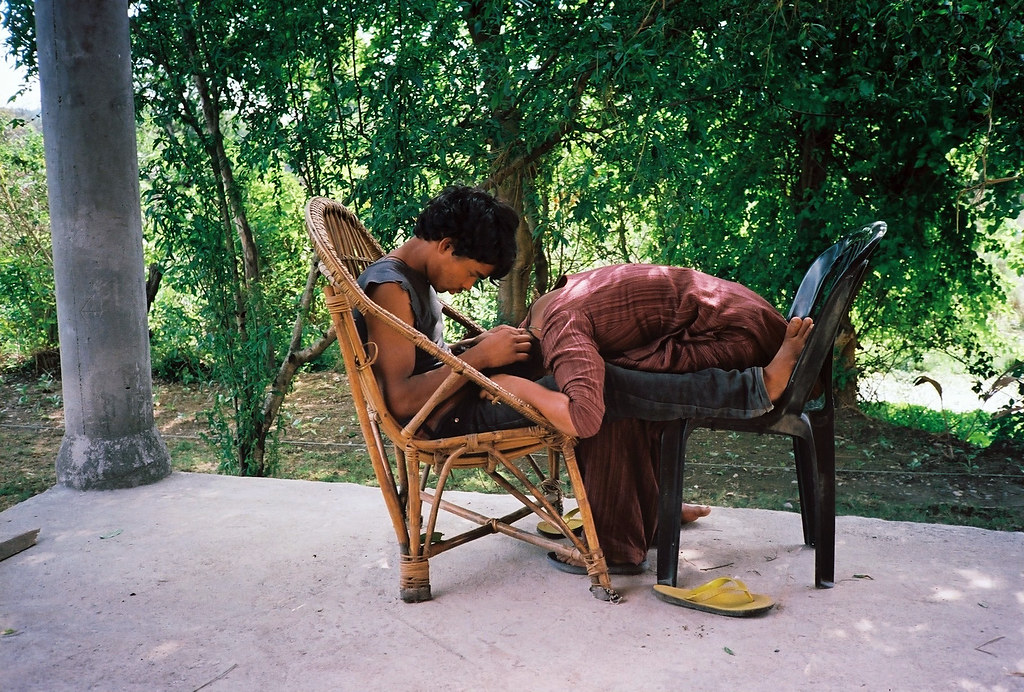

When they weren't cooking Khayam was jumping on Angus' back, throwing rocks at fish, using Kalphunas headscarf or tunic-dress as a tea towel to dry his hands, and finding other ways to wind her up, mostly while smoking a bidi and laughing loudly. When they weren't cooking Kalphuna washed their clothes at the pump in the garden, swept the floor, and wrestled Khayam on the lawn with surprising force. Behind laughter at Khayam and his ways, she had a permanent trace of hopeless exhaustion in her furrowed brow. They spoke little English, but called us their brother and sister. We asked Khayam's age and Raju laughed and said it changes with the weather.

When Angus introduced himself, Khayam pulled a face that said '...What a silly name!' and from then on Angus was 'Gyyyaaan'.

He'd bring us food and before the fist chapati had reached our mouths he'd shout from the kitchen 'Gyaaaan… Rice?… Dal?' (do we want more rice and dal?), refusing to eat anything himself until he was certain we were finished. 'Shopping' was 'washing'… 'No water, no shopping!' and 'listening' was 'sleeping'... 'Goodnight brother sister, good listening good listening'. 'Tomorrow' when he meant 'yesterday', the words and concepts are basically the same in Nepali. Pouncing on Kalphuna, 'Kalphuna!!! tounge kiss!!!'.

8am morning chai, sitting amongst blue pigeons with red beaks and pink chests, turquoise fly-catchers with black zoro masks and the occasional golden oriole. After chai Raju took us for the daily walk up or down stream, following elephant tracks and dung. The river, that was then more of a good-sized stream than the gushing torrent that it is after monsoon season, wound through its wide, boulder-strewn, river-bed ghost. Children herded water buffalo amongst the boulders, crossing through the water to narrow, undergrowth tunnels into the jungle. Tunnels from which women emerged with sling-fulls of firewood. We watched Kingfishers watching us; arrows of orange and blue diving over our heads to catch fish. Fish-in-beak, landing on a rock and repeatedly slamming the fish down in a brutal, blood-splattering performance. We met a buffalo herd and noticed the young herders had stopped; two male buffalo were locked horns. We cringed at the deep thud of their skulls colliding. Equal and opposite force pushed them to their knees, holding them snorting and still for what seemed like an eternity. We blinked and one gave way, turned and ran, followed by the other, towards us and the rest of the herd. Two angry, charging buffalo bulls sent the rest of the herd scattering and us flapping and looking to Raju for some indication of WHAT THE FUCK DO WE DO. Raju opened his shawl wide like Batman and moved slowly towards the oncoming bulls who veered off and into the trees towards the village, with the herders sprinting and shouting behind.

After our morning jolly around Animal Kingdom, Raju would walk to the mud and straw homes next door, where the water buffalo herders live, and come back with a silver jug of fresh buffalo-milk lassi, for breakfast, with aloo parathas. Lunch and dinner were either chapati and dal, or vegetable curries, with big handfuls of fresh coriander, and watercress, which grew in vigorous abundance (like everything else there) in the spring between the village and the jungle.

Raju's father, Swaren Singh, walked slowly across the fields along the irrigation channels with Jimmy, the fattest black lab we'd ever seen. He sat silently with us, sunshine-eyes, while Jimmy puffed and slapped her drooling chops on our legs. Khayam made a joke and Swaren Singh whipped up his stick like a sword, swinging it at Khayam who dodged the strike and hugged him from behind.

The 5pm buffalo line, emerging from the jungle to return to their straw-mud homes, pretty much holding the tail of the one in front between their teeth. A flurry of stampeding hooves overtook them, and us, charging through the river and into the yard; 15 water buffalo calves, spooked by something and back to safety. A toddler not more than two toddled amongst them, clinging to their fur for balance.

Under shelters at field corners, farmers slept next to small fires, on look-out to keep elephants off the crops. One night after dinner, word spread that there was an elephant in the river and we all ran up to the balcony to try to get a look. We didn't spot it, but it was there, doing its thing...

Raju moved calmly and quietly. He radiated a gentle kindness and his whole body bounced with his deep belly giggles. He didn't speak much. He had a multitude of ways to wrap his blanket around him and gave mighty bear hugs- he'd been a champion weight-lifter/wrestler. He laughed at any bodged job or semi-working piece of equipment, declaring ironically, 'It's ok!… made in India!'.