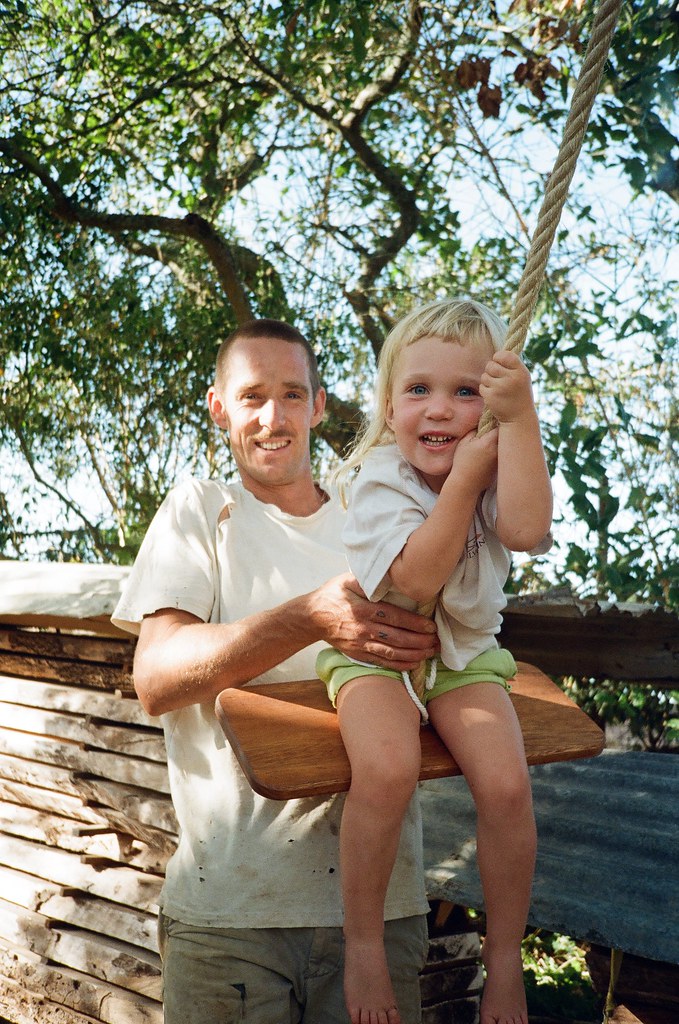

The first memory I have is of waking up in a room that I didn’t recognise, seeing individually my mum followed by my partner Angus, followed by my sister Grace, who were crying as they were squeezing my hand, gently explaining what had happened and telling me how happy they were that I was alive. I asked if Frida, our 3 year old child, was ok. I learned later that asking, 'Where's Frida?', was all that I had done from when they had stretchered me out of the car and put me in the ambulance, up until I went into surgery, but I don’t remember any of that. I responded suspiciously to Mum, Angus and Grace’s assurances that Frida was fine and at home with Grumpy. I had been alone in the car, Frida hadn't been in it. Their skin was bright yellow and everything was happening on repeat, three times. I thought that they might be visiting me in a fourth-dimensional world, I didn’t believe that they were real.

Later, a man who introduced himself as my chief surgeon, also with bright yellow skin, told me that he had operated on me but that he had been unable to save our baby. He told me that the presence of the baby in my tummy almost certainly saved my life by shielding my vital organs from the impact. I asked him where Frida was and told him that it was the third time that I’d seen him. I smirked when he said it was the drugs I’d been on and assured him it wasn’t.

I couldn’t remember, or properly register, at this point, that I had been pregnant. I tentatively touched at my tummy through my hospital gown and it felt flat and empty, I decided, sunken and dead. I tried to move but couldn’t. I decided, dead. Nurses entered and exited. Everything that happened around me, happened three times. The bed rose and twisted and the ceiling morphed, to the sound of background hospital machine beeps. I pulled the blood-oxygen reader off my finger which was supposed to signal for assistance, but nobody came for what felt like an eternity and so, now certain that I was dead, in some form of purgatory, I started trying to pull out all of my drug lines so that I could somehow get up and walk to my family and kiss them goodbye, but my body wouldn’t move properly. That must have set off an alarm on a central monitor because someone’s bright yellow face appeared, trying to reassure me. Some time after that, Nina, a face I knew and loved, though also bright yellow. For the safety of patients, visiting hours in ICU have to be short, but after I started pulling out my wires the doctor had called my family, who had just arrived home, to say that I was stressed and that it might be better if someone could be with me overnight. Living over an hour away and unable to get there quickly, family called Nina, a special friend, a doctor, in Lisbon, who dropped everything and came to be by my side. Her calm, loving, continuous presence, followed by Grace’s, who drove back to Lisbon to spend the night with me, kept me sane, and I felt, alive.

I had been in an induced coma for two days. They had performed emergency surgery on my abdomen to locate the source of the internal bleeding. My uterus had ruptured. Our baby was within my body but in the impact of the crash, the wall of my uterus had torn and our baby had been forced out. His heart wasn’t beating. The surgeon removed him, along with the remnants of my right ovary and uterine ligament, and inspected my other organs for serious damage. Some abdominal muscles had also ruptured from the seatbelt impact and needed stitching up along with my uterus. It was, apparently, a full operating room requiring twelve people from four different speciality teams. I had lost a lot of blood, went into hypovolaemic shock and became hypothermic as a result. They kept me in an induced coma while they ct-scanned my body for injuries to my brain or bones, gave me numerous blood transfusions to replace all the blood that I’d lost, and managed to get me stable.

I had a damaged dorsal vertebra that would require stabilising with screws and bars fixed to the above and below vertebra. I had fractures in my pelvis, six broken ribs, a bruised lung, and four broken metatarsals in my right foot. My right boob became so swollen from the milk and bruised from the seatbelt impact that it was almost comical and a nurse’s assistant asked me if I had a silicone breast.

We aren’t a family that follow any formal religion, but when my family went home that first night, after visiting me, unconscious, a tube down my throat with machines breathing for me, wearing a neck brace and covered in heat-pads due to the blood-loss hypothermia, after finding out that the baby had died but that I might survive, they asked everyone they knew, friends close and far, to send their love, thoughts, prayers. Our collective family and friendships stretch quite far so that all around the world people sent healing wishes that night. I awoke from a major vehicle collision and a life-threatening abdominal injury, without the baby that had been growing inside me, but alive.

A ruptured uterus is a high risk factor for maternal death but I am alive.

I don’t have damage to my spinal cord, I don’t have damage to my brain.

Whether it was due to that collective, focused healing, the presence of our baby shielding my abdominal organs, the exceptional medical treatment, or a combination, I feel a gratitude that words can’t come close to. And at the same time, a desperate sadness.

For the days after I awoke, my whole abdomen cramped when I tried to recollect the event, or when someone described to me what had happened. I was apparently conscious until I went into surgery, but my only vague memories were of something huge crashing into my car from behind, the sound of someone’s shout, ‘Ela está grávida!’, and a distant sense of relief to be in a moving vehicle with sirens.

I was a relatively unusual case in ICU with multiple injuries to my body that required attention from different teams, but I didn’t need to be intubated the entire time. Therefore, I could be awake. A lot of the patients that they care for in ICU spend most of their time in an induced coma and usually once awake, after a day or so, are transferred to a different ward. They needed to protect the patients as everyone there was in a critical condition, so visiting hours were very minimal. I was in a side room rather than on the main ward. These factors combined meant that I spent almost all of the seven after-coma day and night times alone, in bed on my back, unable to move my body or do anything for myself without pain, unable to sleep, with nothing to do other than to stare at the ceiling, think about what I could do to get better faster, count down the hours to visiting time, and to try to process the death of our baby. Seven days, it felt like torture. And I think back to the height of Covid and the people who would have been through similar, totally alone, only seeing masked hospital faces, without even minimal family visits. The trauma that people must be carrying.

But I can’t write about the loneliness, desperation and fear without also writing about the kindness that I experienced during the moments that I had company with a doctor, nurse or nurses assistant. Any time someone stood alongside the bed, they held my hand with their gloved hand, and squeezed a little tighter if they sensed pain, fear or sadness. The forehead strokes and kisses, the tears shed with me over what it is to love and lose as a mother. Tender. The nurse assistants who fed me without any sense of haste, we talked about where they lived, what they'd had for dinner, how they'd spent their day off. The daily, gentle bed-baths with warmed wet-wipes, the mini-massages. The time that the nurses observed my rats-nest hair and brought in shampoo, conditioner and combs the following day. A first time for ICU, they washed my hair over the top end of the bed, the soothing hot water fell into a bin bag. They spent an hour combing out the knots and tying my hair into a dressage-pony plait on the top of my head. Tender.

And the kindness of family, friends, neighbours, who rallied around, dropped their plans, flew to Portugal or offered to, called, messaged, cared for our animals and supported my family and I in any way that they could. The kindness was continuous and relentless, a determined life-raft that kept us afloat. Deliveries of delicious home-made food. Every room of the house became brightened with vases of fresh flowers, when one bunch started to wilt, another would arrive at the door, filling the house with scent, bursting, hopeful.

The immense power of the gathering of people in selfless kindness at times of serious need.

On day eight, the day after the operation to insert screws and bars to reinforce my spine, two physiotherapists helped me to move from lying down to sitting and momentarily standing. My whole body wobbled like it had never been used before. The day after, I took three shuffled steps, from the bed to a chair. The day after, with the help of a walking aid, I shuffled out of my room and around the ward. They asked if I was sure that I felt ready to walk but I’m a stubborn bitch.

The clinical treatment that I received and continue to receive in the public health system has been absolutely exceptional. I appreciate more than ever how lucky I was to grow up with the NHS in the UK and to have access to public, free healthcare here in Portugal. After I awoke from the induced coma I was monitored not just by the ICU team but the obstetricians, the neurologists, the orthopaedics, a therapist, a psychiatrist and a physiotherapist. Almost every week since being discharged, I have received phone calls to schedule follow-up consultations with the various departments monitoring my recovery. I have felt so cared for. Free healthcare has it's roots in kindness: we will care for you and try to make you better, irrelevant of how much money you have.

After nine days in the windowless intensive care room in the basement, I was moved up to a post-surgery ward on the fourth floor, with a window. For the first time in nine days I could see the weather, day, night, birds, and when the mist cleared up, a corner of sea. I could see the birth block that we’d visited two weeks previous to scope out in preparation for labour. Sometimes, in the little rectangles of window, I could see people holding their babies.

Our baby Meirion. Our instinct that he was a boy whilst growing for eight and a half months inside my body, confirmed by the surgeon who removed his lifeless body from mine. Our little boy who we were so close to meeting and so ready to welcome into our lives, but who we’ll never get to know in the world outside of my uterus. Who in the previous months had kicked and wriggled with such strength that it took my breath away and I thought his foot might burst out of my side. Our little Meirion, so little and yet so massive. Thank you, for keeping me safe and allowing my life to continue, as mum to your big sister, as partner, daughter, sister, friend. I’m so grateful not to be leaving this world yet, but we’re so, utterly devastated that we won’t get to share it with you, to know you, who you’d have become. We all love you, so much.

After I was discharged from hospital, on the day of your cremation, we were able to see you. Your little wooden coffin looked incomprehensibly small where it sat on the conveyor belt that joined the chapel to the incinerator room. Angus and I stroked your perfect cheek with the back of our fingers, we held your tiny cold hand until it was warm in ours. Your expression was similar to Frida’s when she sleeps. You looked peaceful, almost like you were about to take your first breath, if it wasn’t for the stitched up incision I could see that started just below your chin. Someone had tried to cover it with the white sheet but I knew that it ran right down the middle of your body. Autopsy.

I wanted to protect you, hold you to my chest, keep you safe, bring you home. Our baby. You were healthy, you shouldn’t have died. The conveyor belt powered up and you disappeared behind the curtain. I felt my instinct to mother you like a physical thing joining you to me, me to you, it was being torn in two the further you moved from me. How could I leave you there?

After 14 days in hospital, I was discharged and allowed to continue my recovery at home. Relief was matched with the brutal reality of how the experience had been for my family, receiving that phone call from the accident site, waiting, not knowing, the baby died, visiting me whilst I was intubated and in a coma, not knowing, waiting. I love them so much, witnessing their collective suffering hurts, it tears at my insides.

After becoming a mother for the first time, to Frida, I sometimes felt I couldn’t breathe beneath the roaring weight of postpartum anxiety. Responsible for this tiny life, I had to stay healthy, I had to not die. And now, Frida nestles her face into my neck and tells me, ‘I’m so glad you’re back mumma, I missed you when you were in hosspipull (hospital),’ and my heart breaks and is filled with gratitude all at once. I don’t know what we do with all this love and all the potential pain of loss.

‘I’ve never seen anything like it, she’s so lucky to be alive.’

Said people who saw the concertinaed, crushed state of the car.

Said the surgeon about the imprint of my spine on the back of my uterus from the force of the crash.

CCTV and the police report confirmed it: As I waited to turn left off a road into a garden centre, cars passed around me to my right, like they were supposed to. Then a lorry drove, at speed, without braking, into the back of my car and pushed my car onto the other side of the road, into a head-on collision with an oncoming vehicle. My car was crushed around me, front and back. Nobody else was seriously injured.

Frida’s car seat in the back, crushed.

Frida wasn’t in it, Frida wasn’t in it.

But the image comes to me whenever it feels like it, her crushed car seat. The what if.

Frida wasn’t in it.

My family doctor who had accompanied my pregnancy, hugged me tight. She sat down on the other side of her desk, her cheeks red and eyes wet, into a long, heavy silence and I realised that she was waiting for me to tell her what I needed. I didn’t really know why I’d made the appointment. She asked me how she could help. I don’t know. I just thought I should come here. I thought maybe she needed to see my empty tummy, to inspect the pink scar that runs vertically from my pubic bone up my tummy and neatly around my bellybutton, now free of the 40 staples that held me together. It was my due date and, without a lorry having driven into me, I might have been there with my baby. Instead I showed her my boobs, still quite full of milk despite the tablets I had been taking to inhibit lactation. My right boob was still double the size of my left, a seat-belt strip of green-purple bruise crossed it diagonally. She gave me a paper for an ecografia mamária, advised me to keep taking iron tablets to get me out of anaemia, and, ‘força Holly, força’.

The top of the plastic chair dug into the little bumps on my back where the screws fix into my spine and I fidgeted to get comfortable. A lady with a pram sat down a couple of seats to my left. I tried to find something to look at as her newborn baby made newborn baby noises. It started to cry and I watched her lift it out and hold it’s tiny body to hers. She hummed a song gently into it’s ear, it’s tiny hands clutched at her clothes. On my lap I clutched my discharge notes from the hospital, my eyes caught the words, ‘feto na cavidade peritoneal, sem batimentos cardíacos', fetus in peritoneal cavity, without heartbeat. I couldn’t make my mind move away from my dead baby inside my body but outside my uterus, helpless. I studied the wall opposite me to try to distract myself from crying outside the physiotherapist’s office but all I could hear were the newborn baby noises and all my mind gave me was the image of my dead baby inside my body, outside my uterus. Helpless.

Also, though.

I am so happy to be alive. I love life so fucking much. The leaves are turning orange, rain has arrived and I’m almost as excited as the plants. Our outside shower, with the snails that come out at night, the hot water, my skin, the sky. Cuddling Frida to sleep. My ribs feeling better enough to roll over and lie on Angus's chest. Kissing the soft indent between my dogs' eyes. Breathing in the scent of my sister, mum, dad and all the people I love. Every day, walking gets easier. I should be wearing shoes to support the four broken metatarsals in my right foot but all I want is to feel the earth meet the soles of my feet. I’m here. At dusk Angus and Frida go outside to look for toads and owls and to hear the sound of wild boar chomping their jaws. Frida comes charging in through the door, to hold my face in her cool, dusk hands, ‘MUMMY I SAW A NIGHTJAR!!!', her eyes so alive with joy, so determined to instil in me: this life is so good.

I hadn't been knocked unconscious during the crash, I was awake, and apparently, able to talk, all the way from the crash up until when I went into the operating room, but I don’t remember any of it. If I don’t remember it, is it real?

'If a tree falls down in a forest and nobody hears it, did it make a sound?', a philosophy question I always thought was a stupid one because a forest is never empty of animals. But I guess the question is, is a sound only a sound when it lands on an eardrum? What makes stuff real?

Deep breaths still tug a bit on the broken ribs, real. Scars, real. The absence of our baby, real. The lady who apparently held my head and neck still before the ambulance arrived, real. The memory blank is a protective mechanism, I'm told, my brain keeping me safe. My unconscious is in charge, I'm not in control. If I only have memories of before, and after, but not the main event, I can't seem to write it into the narrative of my life in a way that makes sense. Perhaps that's just it though, it's not supposed to make sense, healthy babies don't usually die at almost full-term pregnancy, lorries aren't supposed to drive into the back of your car.

On a mission to contact and thank everyone who had helped me, I recently googled the chief surgeon who lead the teams that had performed my emergency surgery. I discovered that he is the director of the biggest obstetrics department in the country, perhaps the most senior and experienced obstetrician in Lisbon. He usually works at a different hospital, but the obstetric urgência of that hospital was temporarily closed for renovation, so he happened to be working at the hospital I was taken to and he happened to be on call that evening. I couldn’t have been in better hands. I emailed him to thank him for saving my life and despite all the important medical stuff he has to do, he replied. He was kind. He said that the accident had had a big impression on him and the teams. He described it as brutal, devastating, the worst he’d ever seen in a pregnant woman.

He arranged for me to have a consultation with him a week later. He and his colleague want to write a paper about mine and Meirion's case for the British Medical Journal. Many surgeons would have performed a hysterectomy but, his colleague said, thanks to Dr Alexandre's experience and knowledge, they were able to repair my uterus. They want to help educate other medical professionals about what is possible.

He said, 'In accidents of pregnant women even less brutal than yours, we would be lucky to find the mother alive. Here, we had a lot of luck.'

Can something be a miracle and a tragedy all at once?

I am so lucky. I am alive, drinking mugs of bone-broth that we'd pre-made and frozen for post-partum healing. Collagen. Now I need healing for different reasons and I wonder how collagen works on grief, on trauma.

To be absent of a baby in my arms, after growing one inside me for almost nine months, bewildering.

Be-wilder: to be thoroughly lead astray.

I'm empty and wild and a part of me will forever stay this way, scrambling, hysterical, astray, 'but where's my baby?'

Hysteria, from the Greek hystera: uterus.

Female hysteria,

woman, I understand you.

After a routine caesarian the advice is to wait, at the very least, six months before becoming pregnant again. After a uterine rupture, at least a year. A following pregnancy should be carefully monitored and delivery performed by elective caesarian at 35 weeks.

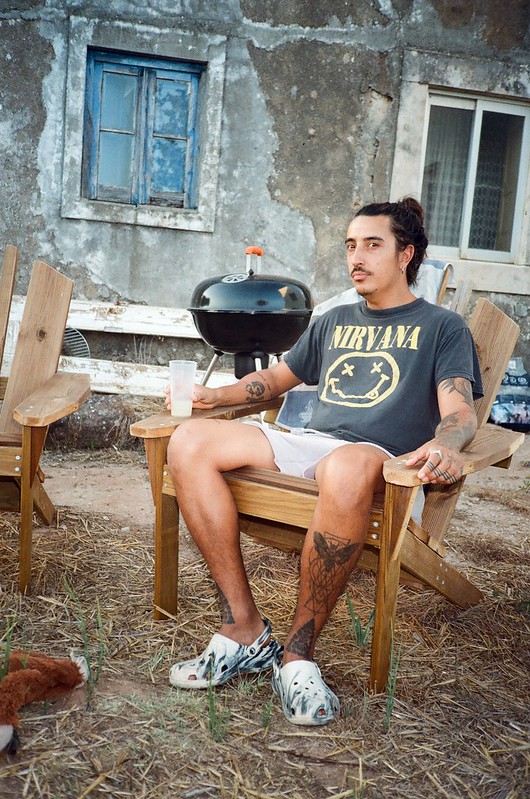

Meirion can't be replaced, but something good must come of this. So we continue, because by not continuing we'd be letting him down, and Frida, and the osteoclast cells that have been studiously repairing my broken bones. With the time that we thought would be filled with newborn baby care, we immerse ourselves in creative projects (photography - hollygable.eu and furniture - @angus.fulton) that we had put on hold for the post-baby years.

An osteoclast cell. Credit: Nanoclustering / Science Photo Library

F033/5743

F033/5743

And there are good things that come of shitty life happenings, of grief and trauma. They unite people like a mutual friend that you can't be without. You only really know grief and trauma, when you know grief and trauma. You only know the magnitude of love that a parent feels for their child, when you know it. And our day will be spontaneously softened by someone who, before the accident, we'd spoken to just a handful of times. We're almost strangers, I don't think our bodies have ever touched but the contact of your hand, firm on my arm, communicates it all. The tears that suddenly can't be contained by your eyes. You know. You know that these feelings wont go, but life will grow around them. And humans, we'll be here for each other.

Our beautiful friends continued with the food train that they had offered as a post-partum gift at the surprise baby shower that they had thrown for us in August. Food packages arrived at our door every Sunday afternoon. The requirement for the food train had shifted from newborn-baby-chaos to baby-death-emptiness but the generous love from our friends and family perpetuates.

Love perpetuates. For all the sadness and loss, at every stage of this nightmare journey the way forward has been illuminated by an inexorable glow of love and kindness, preventing the darkness from enveloping all and everything.

I love you.

Thank you.

Be kind.

Be kind to strangers or otherwise, and particularly to sick or vulnerable people.

Support free, public health care.

Love life.

Love life as hard as you can.

Love life as hard as you can and tell everyone.

Tell everyone.

Tell everyone you love.

Tell everyone you love that you love them.

Tell everyone.